Collector Roland Sabates has filled his Oak Street Mansion art hotel with works that reflect his passion for regional art.

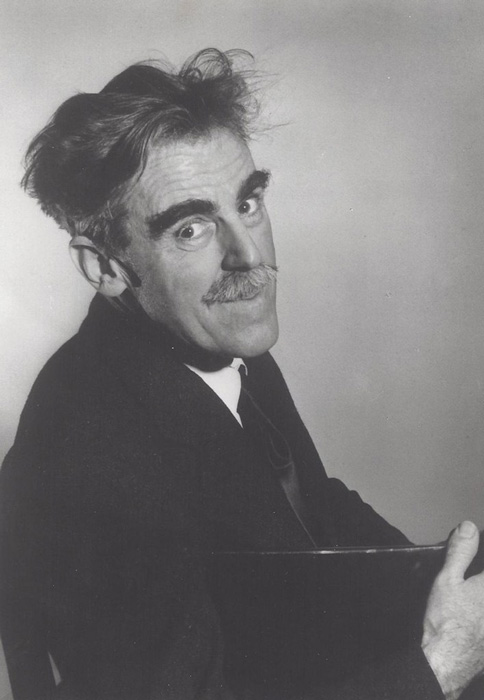

(photo by Jim Barcus)

His current pursuit is Ross Braught, a noted artist and muralist who was head of the Kansas City Art Institute’s painting department in the 1930s.

Roland Sabates is an ophthalmologist and passionate collector of American, African and Latin American art. In 2013 he opened Oak Street Mansion, a bed and breakfast which displays part of his collection and doubles as an exhibition space for temporary shows which he curates. Sabates has also authored several books and is currently researching the artist Ross Braught; he hopes to publish his findings later this year or in early 2017.

Although Ross Braught (1898-1983) was born and died in Pennsylvania, he taught at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1931 to 1936 and again from 1946 until his retirement in 1962. He was a masterful printmaker and talented painter; Thomas Hart Benton referred to him as “the best draftsman of our generation.”

What is the first thing you collected? Were you interested in art as a child?

can be seen at the Music Hall in Kansas City’s

Municipal Auditorium.

I started collecting African art — you collect what you can afford. But I had no interest in art as a kid. In 1978, I spent six weeks in Abak, Nigeria, doing a mission. There I developed my interest in their art as it relates to their spirituality and healing.

I really like the regional art here and I think it is under-appreciated. I think the Art Institute should have a museum that honors the artists that graduated from and/or taught there. There are a lot of great artists who have worked in Kansas City.

How did you first get interested in the work of Ross Braught?

There was a lithograph of his in an auction about ten years ago and I was intrigued by the trees; it was inscribed “Marina Cay.” I bought it and started learning about him; I discovered that he was very prominent in Kansas City.

I had seen Braught’s Mnemosyne and the Four Muses (an enormous work at the Music Hall in the Municipal Auditorium) but I had never really paid attention to it.

Where have you found most of his works?

He studied at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art and they own two of his works. The Nelson-Atkins owns an important landscape and his paintings and prints can be found in other museums as well. Most of the ones I have purchased have been from small auctions or private collections. His works are very hard to come by; he was always reluctant to sell his work.

Did the pictures stay in the family?

When he went to Philadelphia after he left Kansas City, he stored all his works in an attic for years. Before he died, the paintings were unstretched, rolled and shipped in cylindrical containers to his son, Gene. However, his son put them in his attic without opening them.

David Cleveland, who wrote about the artist in 2000, had tried to find works by Braught. Cleveland finally managed to locate Gene Braught and asked him if he had any works by his father. He said he had some tubes in the attic but did not know what was in them. Cleveland kept insisting that there must be some work somewhere. After his son discovered the packages were full of paintings, a New York dealer purchased them. Most have been sold. Not many are available for sale but there have got to be more works out there.

Perhaps from writing the book, more works will come to light. This project on Braught fits in with your interest in regional art.

I previously wrote a book on Charles Wilimovsky, but this book is going to be more extensive, with reproductions of works from other museums and all of the known works by Braught.

Braught lived in the Caribbean for nearly a decade. You went to Tortola earlier this year to do some research; what new information did you find there?

I found out where he lived, found the house where he lived. A lot of his drawings had been inscribed “Marina Cay.” Marina Cay is just an eight-acre island that was owned by the writer Robb White. He and his wife purchased the island in 1936 for $60. They built a house out of concrete, not very big but it could withstand hurricanes. They lived there for a short time; then his wife got sick and they had to go back to the States. In the meantime, World War II broke out and White was drafted. In White’s memoir, Two on the Isle (which was made into a movie), he writes that he left the wandering artist Ross Braught to island sit for him.

Braught also did a big mural in Puerto Rico for the officers’ club at Fort Buchanan. Unfortunately the building was torn down and the painting was destroyed.

Another mural — that has been protected — is in Waynesboro, Mississippi. It is in the post office and is a WPA work. Braught entered the competition, won and got to do the mural. I went there and took pictures of it.

Braught moved around quite a bit.

He went to the Grand Canyon and did a lot of lithographs and paintings. The last places I need to go are Woodstock and Provincetown. Woodstock is where he learned lithography. He studied under Bolton Brown, who taught and wrote important books about the subject.

When Braught came back to Kansas City in 1931, he got a job to run the painting department at the Art Institute. He was demoted when Thomas Hart Benton arrived to work there; Braught went to the Virgin Islands and did not return for eight years. Later, he returned to the Art Institute until he moved back to Philadelphia, where he lived as a recluse.

Braught was an unassuming guy, a real gentleman, never spoke ill of anyone, and he did not care for fame or money. (He was) really introverted, strictly all about painting. No small talk or chitchat, but if you look at his work, it is really quite impressive.

Are there any lost works you would love to find?

The lino-cuts he did in Provincetown are all studies for paintings. There is one print titled Provincetown, but the painting’s location is unknown.

Tell me more about Reflecting Pool, the painting you bought in Chicago.

He did a lot of things for himself, not for sale. When the army hired him to do the mural in Puerto Rico, he went to Suriname, Dutch Guiana to study the people there. He was so impressed by the women going into the forest, to a water hole where they would get water. He wrote his father a letter about how the vegetation had stained the watering hole the color of coffee, making a perfect mirror. He called this painting Reflecting Pool, and you can see the woman’s image being reflected. He painted it when he came back to Kansas City in 1949.

The exhibition of 24 works by Ross Braught is currently on view at the Oak Street Mansion, 4343 Oak St., through the end of the year. For more information, email Roland Sabates at rolandsabates@aol.com; he would also be interested to hear from those with Braught works of art or further information on the artist.