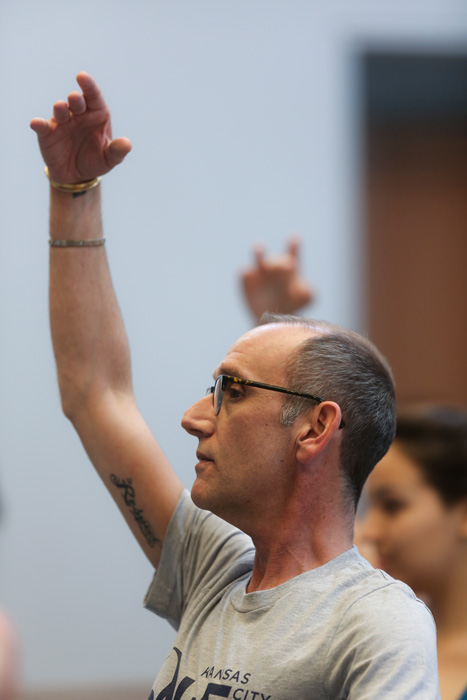

Jason Seber, David T. Beals III Assistant Conductor for the Kansas City Symphony

Jason Seber (pictured above) starts his first year as assistant conductor for the Kansas City Symphony with a full schedule and an attitude to inspire teamwork and embrace challenges.

One of Seber’s earliest musical experiences was watching E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, the very first non-animated movie he’d ever seen in a theater. “I remember the scene where Elliot and his friends are flying through the sky (and) feeling like I was literally being lifted out of my seat in the theater, and it was because of the music,” he said.

Music can really sweep you away and change you and have an impact on you.”

Jason Seber, Assistant Conductor for the Kansas City Symphony

“It definitely ingrained something in me even from a young age, that music can really sweep you away and change you and have an impact on you,” he added.

Seber will conduct the E.T. score live with the film — “quite possibly my favorite film score of all time” — during his first season with KC Symphony as part of the “Screenland at the Symphony” series. That’s just one of his many responsibilities which include conducting pops, family, education, holiday, and special concerts, like the “Classics Uncorked” series. A trained violinist and music educator, he was previously education and outreach conductor for the Louisville Orchestra and music director of the Louisville Youth Orchestra in Louisville, Ken.

But it was an early dose of conducting that ignited his passion for music: “One day, my orchestra teacher was sick. . . . the substitute did not want to conduct and the kids said, ‘let Jason conduct us,’ since I was sort of the class clown. I kind of faked my way through it, but I knew what a 4/4 pattern looked like and I could keep a steady beat, and I loved it.” When his teacher heard about it she let him conduct a piece in a concert that year.

“Some people make their debut conducting Mahler,” he laughed, “I made my conducting debut in eighth grade, conducting the Love Theme from St. Elmo’s Fire.”

The experience, he said, “totally changed my whole view of music in general, because I saw what goes into music, and (I wasn’t) just thinking about my single violin line, but starting to understand how all the parts fit together and the different things you have to think about.”

Along with music, Seber’s passions are cooking and sports. “If I could have a second life and second career, I would want to be a chef. It’s demanding, just like being a conductor. But I think it’s a lot of creating and taking something that already exists . . . but finding different ways of combining ingredients in ways that people have never thought of. It’s the same with music. All the notes and all the dynamics are all right there but what do you bring to it that maybe someone else has never thought of?”

And while Seber admires great conductors like Carlos Kleiber and Leonard Bernstein, he also finds inspiration in great coaches. “You have all these extremely talented and extremely knowledgeable people you get to work with. How do you get the best out of them? How are we all going to work together to be as successful as we can possibly be?”

Harlan Brownlee, Executive Director of Kansas City Friends of Alvin Ailey

As a child, Harlan Brownlee wanted to learn to fly.

“Flying takes extreme focus and relaxed concentration,” Brownlee says. “It requires a thorough understanding of the science behind the airplane, its instruments, the aerodynamics at work, and the weather. But that knowledge is useless until integrated and properly applied. There is an incredible feeling of accomplishment and satisfaction that comes from the take-off to the landing. I often refer to flying as the small dance.”

Brownlee has had his pilot’s license for almost 30 years. For those same 30 years, he has been applying the same discipline and insight it takes to fly to his work in the arts in Kansas City: He spent 13 years as the co-artistic director of City in Motion Dance Theater, four years as the leader of Kansas City Young Audiences, and six years heading up ArtsKC.

Now Brownlee finds himself with a new agenda to set as the executive director of Kansas City Friends of Alvin Ailey.

“Kansas City Friends of Alvin Ailey has an amazing story to tell,” Brownlee says. “It’s a story that goes far beyond simply presenting the Ailey companies each year, and very few people in the community really know about it. Through classes and outreach, we reach 25,000 children every year. The children and young people who participate in the program ultimately learn life skills that will serve them their entire lives and help them to make smart life choices, and when our kids are making smarter and better choices everyone in the community benefits.”

Brownlee’s career in the arts, though it has spanned several disciplines, started with a love of dance.

“Working as a professional dancer, choreographer, and teaching artist I came to see the power that the arts had to create a true sense of community and connection. Becoming a part of that and experiencing it firsthand has had a tremendous influence on me,” Brownlee says.

Kansas City Friends of Alvin Ailey was founded in 1984, designed to function as a second home of the New York-based Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. The company travels to Kansas City every fall for performances, traditionally at the Folly. This season, Brownlee is adding a venue and a potential audience.

“We’ll present Ailey II this fall at the Folly, but then in spring 2017, we’ll present AAADT at Johnson County Community College, Yardley Hall. I think there is an audience in Johnson County that will love seeing Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.”

But Brownlee seems most excited about the outreach programming.

“I recently attended an open house for our AileyCamp,” he said. “At AileyCamp the students participate in dance classes, as well as classes in creative writing, percussion, and personal development. What struck me, and made a deep impression on me, was the rigor and discipline that I saw the students demonstrate. Watching those classes and the work of the students and instructors was inspirational. It is what I love most about my work at KCFAA.”

KCFAA is likely to receive a boost in the coming months. In April, the city council approved a plan for revitalizing the 18th and Vine district. The plan includes a new headquarters and performing space for KCFAA.

“We are now poised to expand our programming and fulfill the strategic plan,” Brownlee says. “Having the resources to expand, being able to fine-tune our message, and demonstrating KCFAA’s value to the community — that’s what is most exciting to me.”

Cheptoo Kositany-Buckner, Executive Director, American Jazz Museum

In January 2016, followers of Kansas City’s jazz scene were greeted with the news that the American Jazz Museum would soon have a new Executive Director: Cheptoo Kositany-Buckner, who assumed the position in March.

Prior to joining AJM, Kositany-Buckner worked for the Kansas City Public Library, including the last 11 years as deputy director. She began her career working with technology after attending Central Missouri State University, eventually moving into administrative work.

Kositany-Buckner traces her background in the arts to growing up in Kenya.

“Music and dance are part of being African. A child is born, someone gets married, and there is music. The arts are infused into life there.”

And since coming to the U.S., she said, her appreciation for the breadth of art has grown. “Art should be part and parcel of who we are as human beings because art is a way to connect people; it speaks to all of us on a very basic level.” She practices what she preaches, designing jewelry and occasionally showing it publicly.

As an example of art’s power to connect people, Kositany-Buckner points to the exhibit at AJM’s Changing Gallery through Sept. 30, “Jazz Speaks for Life: Discover the Civil Rights Movement through Musical & Visual Expression.” A number of works in the show address civil rights in provocative ways. And the way the show was organized also speaks to equity and inclusion, featuring Kansas City-based artists on equal footing with nationally and internationally prominent artists such as Charles Bibbs and Ed Dwight.

Dwight’s Maasai Women sculpture in the exhibition holds particular meaning for Kositany-Buckner. She explains that some Maasai live in her home country of Kenya, and that seeing a work inspired by them in an exhibition focusing on civil rights struck her very personally, as if these figures are kindred spirits joining with her in her work at AJM.

Central to that work is the launch of First Friday activities on 18th Street as a way to end the isolation of the 18th & Vine area from the Crossroads and offer opportunities to artists who have not previously had a place to show.

Kositany-Buckner’s loftiest goal may be to return a major jazz festival to Kansas City, currently slated for Memorial Day 2017. It’s an event sure to come with attendance, programming and funding challenges, but she is determined.

Kositany-Buckner also wants to raise local appreciation for Kansas City’s place in jazz history and to position the American Jazz Museum to garner as much attention locally as it does nationally and internationally.

Making jazz more accessible to a greater variety of people is also a goal, and Kositany-Buckner is pursuing multiple strategies to make that happen. One is to increase digital access to the museum’s collections. In September the museum will offer a free jazz academy to introduce young musicians to playing jazz. In November, Ted Gioia, author of How to Listen to Jazz, will visit the museum as a guest speaker and address general audiences.

Going forward Kositany-Buckner has her eye on several big-picture questions: How do we infuse jazz perspectives into the STEM/STEAM dialogue? How can we expose young people to career paths in music other than performing or teaching, such as sound engineering or publishing? What does a museum look like in the era of gigabit-speed computing networks?

Whether she’s looking at immediate priorities or focusing further into the future, it will be exciting to participate at AJM as this dynamic leader’s visions are fulfilled.

Amy Kligman, Executive/Artistic Director, Charlotte Street Foundation

Creativity was woven into family life during Amy Kligman’s growing up years in small-town New Washington, Indiana. Her mother was a florist and cake decorator who did folk ceramics; her grandmother made quilts. Neighborhood arts programs also helped lay the foundation for Kligman’s eventual decision to go to art school, and in 2001 she graduated from the Ringling College of Art & Design in Sarasota, Fla., with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in illustration.

After a stint at American Greetings outside of Cleveland, Kligman moved to Kansas City to work at Hallmark Cards. She initially made her mark on the Kansas City art scene as an artist, showing her studio work at Paragraph and Leedy-Voulkos Art Center, the Kansas City Artists Coalition and Block Artspace. In 2014, she exhibited a large body of her whimsical paintings and mixed-media works at the Nerman Museum as one of that year’s Charlotte Street Foundation visual artist fellows. But all along, Kligman was also developing her administrative abilities, writing grants and organizing shows as a founding member of the artist-run Plug Projects from 2011 to 2015.

“Art gets interesting, when people who don’t normally share thoughts and space get together.”

Amy Kligman, Executive/Artistic Director, Charlotte Street Foundation

When Michelle Grabner, a high-profile artist, educator and curator with a history of involvement in arts project spaces, spoke at the Nerman Museum in 2012, the idea that “it is possible to be an artist, a mom, an art administrator and an arts educator” clicked for Kligman.

These days, she has embraced multiple roles, making art, caring for her 2-1/2-year-old son with her artist husband, Misha Kligman, and working full time as executive/artistic director of the Charlotte Street Foundation.

Kligman’s hire for the top post is emblematic of a significant shift at Charlotte Street, an organization founded in 1997 by businessman David Hughes and administered for much of its history by writer and curator Kate Hackman. From its inception, Charlotte Street served artists, providing money, space and other resources. Now it continues that mission, but it is also run by artists, who make all of the decisions related to grants and programming.

A key part of Kligman’s plan for the organization is “to bring new voices to the table.” “Art gets interesting,” she says, “when people who don’t normally share thoughts and space get together.” Her push is outward, exchanging the traditional focus on the gallery’s white cube to neighborhoods and “places people talk to each other.”

Charlotte Street’s 2016-2017 Curator-in-Residence, Lynette Miranda, who has worked for leading creative ventures including Creative Time and ART21, was selected to help further these goals. “(Miranda is) a relationship builder,” Kligman said, who will “seek out stories and points of view that need a voice and need a place.” Announced in May, a $15,000 National Endowment for the Arts grant — Charlotte’s Street’s first — will help support the program.

Also coming to fruition are two pilot residencies, one neighborhood artist residency designed to engage people where they live, and another offering space to artists launching innovative collaborations.

In 2017, Charlotte Street will celebrate its 20th anniversary with a city-wide exhibit and other programs. There’s always a lot going on, but somehow Kligman manages to make time to build forts on the floor, read Dr. Seuss and visit the Rabbit Hole children’s book center, not to mention indulging her love for “art-obsessed” travel.

Parrish Maynard, Ballet Master, Kansas City Ballet

When Parrish Maynard was nine his diving coach suggested he take some dance classes to help improve his diving form.

“I took classes to be a better diver,” Maynard recalls. “Then I went to see a family friend perform Clara in the San Francisco Ballet’s The Nutcracker. I saw all the children on the stage and decided that was it! I started ballet classes and never stopped.”

Maynard was an only child and very shy; dance became one of his most effective methods of communication. “Dance was a means of self-expression,” he says. “I learned to talk with my feet.”

Maynard went on to dance with the San Francisco Ballet School, the Joffrey Ballet, and the American Ballet Theatre School. He was on the faculty of the San Francisco Ballet School and was a guest teacher last season with the Kansas City Ballet.

This season, Maynard joins the Kansas City Ballet artistic staff permanently as the ballet master.

A ballet master traditionally leads a daily company ballet class and rehearses ballets that the dancers will perform. Maynard’s love of teaching and leading dancers through the formative challenge of becoming a dancing artist makes him uniquely qualified for this position.

“My most transformative experiences in the arts have always involved learning — watching a student transformed into a dancer and an artist. I’m very lucky to be able to experience something like that every year with my students,” Maynard says.

Maynard learned his love for developing dancers from one of the best; he was one of the last dancers hired during Mikhail Baryshnikov’s tenure as the artistic director of the American Ballet Theatre, which ended in 1989. “Misha cared a lot about talent, and he molded it,” Maynard recalls.

The Kansas City Ballet’s 2016-2017 season includes another link to Baryshnikov. In April 2017, the company will mount a production of The Sleeping Beauty. “Sleeping Beauty was the first full-length ballet I did at American Ballet Theatre,” Maynard says. “I was coached by Baryshnikov himself. It was a wonderful experience, and I look forward to passing on all my learning and experience to the dancers at the Kansas City Ballet.”

The ballet world almost lost Maynard when he retired from the stage in 2005. He launched a career as an interior designer and spent a year pursuing opportunities in that field. But he missed dance.

“I trained my whole life as a dancer and I finally realized my job was now to pass on that information,” he says. “To aid young dancers to be the best that they can be and make them better dancers and better people, that’s why I do what I do.”

Bruce W. Davis, President and CEO of ArtsKC

Bruce W. Davis has a long career in arts organizations, spanning the country from Brooklyn to San Francisco. For the last six months he’s been the new president and CEO of ArtsKC, but by his own admission he’s an “accidental arts administrator.” Over 30 years ago he set out to be a songwriter, and as he says in the lyrics of his 2010 song Arts Administrator Blues, “Well the critics rave and love us, but our books are a mess. I confess. I’m an artist, not a businessman. Tell that to the IRS.”

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Davis grew up thinking everyone’s dad owned a kiln, as his own father was a painter and ceramicist. Starting in the fourth grade, he entered an experimental music education program. He wanted to play drums, but had to settle for a trumpet when the funds for a drum set never materialized.

As a teen and young adult, Davis continued playing in bands and became a songwriter, scoring a hit with his song The Girl Every Love Song Sings Of, which reached No. 5 on the Irish music charts. It was around this time Davis became involved with the Brooklyn Arts Council as a registered songwriter.

When he moved to San Francisco, he went looking for a similar artist registry. When he couldn’t find one, he and some friends started their own. This led to one arts administration job after another. For over a decade, he was executive director of the San Francisco Ethnic Dance Festival and then for another 18 years he was executive director of the Arts Council Silicon Valley, where he grew the non-profit into one of the largest arts funders in California.

Following that, Davis helped create Artsopolis, a company which creates online arts and cultural calendars for cities across the U.S., customized and rebranded for the needs of each client-city. He hopes to bring this software to KC. While Davis is impressed with local art, praising Heidi Van’s one-woman performance as Marilyn Monroe in the Fishtank’s recent production Marilyn/God as a “tour de force,” he has some criticism of the area’s arts infrastructure.

Davis has positive things to say about Missouri Governor Jay Nixon and the state-run Missouri Arts Council and also KC, Mo. Mayor Sly James and his Mayor’s Task Force for the Arts, but he notes that the state of Kansas doesn’t seem to have any equivalent arts agencies or committees and likewise doesn’t fund arts and culture. “It’s a crime,” he said. “If I could add an 11th amendment to the Bill of Rights, it would be the right of cultural expression.”

While Davis probably won’t have any luck amending the Constitution, he and ArtsKC will continue filling the gap left by government. The ArtsKC website boasts that he has secured “nearly $50 million for the arts over his career.” But Davis is more than a fundraiser, he describes his job as “PSA: promoting, supporting and advocating for the arts” and cites a variety of ArtsKC’s grants, economic studies and professional development programs.

It seems fitting that a boy who had to play trumpet when his school couldn’t afford a drum kit, is now in the business of fundraising and funding the arts. Someone has to do it: Artists are too busy making art. It’s like Davis sings in his song Arts Administrator Blues, “I said my friends are all dancers, musicians and clowns. Oh, but now I wish I had one who was a CEO downtown.”

Catherine Futter, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Catherine Futter grew up in New York City in the 1960s when it was a hotbed of experimental culture. The worlds of film, theater, photography, poetry, and the visual arts mixed uninhibitedly in street “Happenings,” performance art, video, film and the printed word. Cultural boundaries were meant to be transgressed, and they were.

“We have a very team approach here; nobody does anything alone.”

Catherine Futter, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

“My family background stressed that we should always be learning. My mother regularly took me to groundbreaking shows of 1960s art and that formed my idea of what a museum is,” Futter recalls. She credits this early stimulation as one reason she relishes her new post as director of curatorial affairs at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which she began this past January.

In 2002, when she was hired as the Nelson’s senior curator of architecture, design and decorative arts, Futter was the right person at the right time for the Nelson-Atkins. In America the decorative arts, typically dismissed as fusty, were finally starting to emerge from the subterranean depths of museum basements and being re-evaluated from both intellectual and visual standpoints. Futter catapulted her department front and center by organizing such groundbreaking, traveling exhibits as “Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs, 1851-1939.”

She also loves working with contemporary art and artists, and wanted more viewer participation with shows. In 2010 she curated “Clare Twomey: Forever,” the first one-person exhibit in the U.S. for this British ceramic artist. Futter worked with Twomey to create an interactive show where visitors could negotiate to own one of Twomey’s ceramic cups by signing a “Deed of Gift.” “I still see Twomey’s cups when I go to people’s houses,” Futter said, “and it’s touching to see how well they’re cared for.”

Futter received a Bachelor of Arts in Medieval and Renaissance Studies from Duke University in 1981. She then volunteered for nine months at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, working full-time in the decorative arts department. “In two weeks I knew exactly what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I loved the energy and the collaborative nature of the job; it was also an endless area to research so one could never get bored,” Futter says.

Next she worked in London with Sotheby’s, which was “very hands on,” Futter says. In 1993 she received a Ph.D. from Yale, at that time the only place in the U.S. where one could get a doctorate in the decorative arts.

Futter’s new post is all-encompassing. She oversees the entire curatorial staff including the hiring, and the departments of conservation, education and registration report to her.

“I’m going to continue to elevate the role of the museum, support the curators, and assure the quality of all projects at the Nelson, but,” Futter stresses, “we have a very team approach here; nobody does anything alone.

“It’s a museum’s responsibility to make the most esoteric objects accessible to all kinds of audiences,” Futter says. “That said, there are days when the Nelson is not just a contemplative place — it can be many things to many people during many different times.”

Tony Jones, President of the Kansas City Art Institute

Tony Jones is leading Kansas City’s oldest school of fine arts and design into a transformative future.

“I’m very interested in the transformative experiences,” Jones says. “What is the tipping point? What is it that makes you change? What is it that changes your work?”

Jones was a retired chancellor of the School of the Art institute of Chicago when he took over as interim president of the Kansas City Art Institute in December 2014. A few months later, big improvements were being planned after the school received an unprecedented anonymous gift of $25 million. In October 2015, Jones was named the school’s 24th president.

“I’m shocked and delighted by the depth of what’s here,” Jones says. “This is not a very big city, but you have everything you could possibly want. That’s what we say to the students: It’s not just what happens in these studios. Start looking at what’s out there — music, theater, dance, poetry, jazz and all the other things that you want to support your ideas.”

With Jones at the helm, the venerable institute founded in 1885 has beautified its surrounding natural landscape, finished renovating its Richard J. Stern Ceramics Building and built more convenient parking for visitors. It has also fashioned a new outdoor performance art pavilion/social space and restored Vanderslice Hall, the historic architectural centerpiece of the campus located in midtown Kansas City.

“You can’t undo a first impression,” Jones says of the 21st-century facelift. “That’s why we’re spending a lot of time on what we call ‘the welcome mat.’”

Yet the most vital addition in support of Jones’ modernized vision of KCAI has been the construction of the David T. Beals III Studio for Arts & Technology, where artists are now able to contemplate and create in cutting-edge style.

“It’s about being relevant,” Jones says. “When students walk into our studios, they see all of the technology, all of the equipment, everything from high-end digital routers to a bronze foundry to high-end digital cameras to 3-D printers.”

As a child raised in an extremely remote part of Britain, Jones didn’t get to see any works of art in color (not even in books) until the age of 12, when he was astonished by what his eyes beheld at the National Museum of Wales.

“I walk in and there are the Impressionists,” Jones recalls. “And, first of all, I think: ‘Did a human being do that or did some god come and do it?’ I had never seen anything like that. I was completely changed in a split second. I needed to work out how it was done and see if I could do it, too.”

Jones’ advanced art education began with a scholarship to the University of London, where he was trained to sculpt and paint. His internationally recognized career as a British arts administrator included his selection by Queen Elizabeth II as director of the Royal College of Art, London.

Jones is now leading KCAI’s faculty through a full review of the school’s academic program. The only sacred cow: No sacred cows.

“This is an entirely intimate discussion among high-ranking working professionals,” he says. “These are people who are designers, ceramicists, weavers, painters, graphic designers, animators — all of them sitting down together and saying, ‘What is the appropriate and relevant academic program that we should be offering?’

“That discussion is going to go on for the rest of 2016. It’s going to be a pretty intensive revisualization of where the college is going to go. It’s a major overhaul.”

Photos by Jim Barcus

Pingback:KC Studio Sept/Oct 2016 | Proust Eats a Sandwich