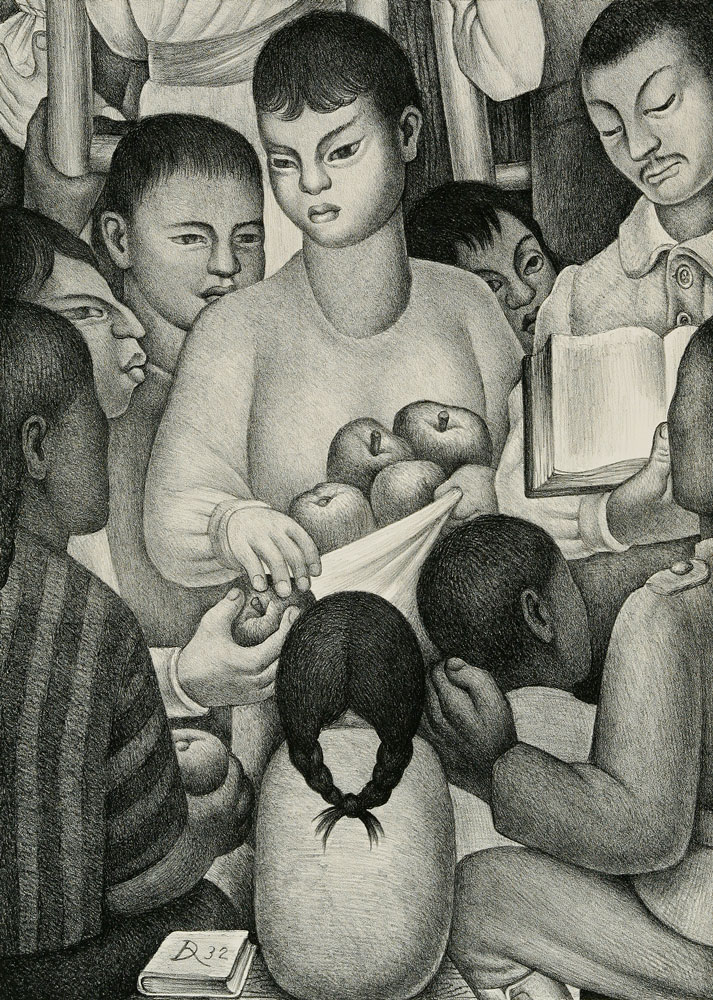

Jean Charlot, Tortillera with Child, Color Lithograph, 1941, 12 1⁄2 x 18 1⁄2 inches

A black and white skull grins blithely, eye sockets empty; on its head sits a bountiful hat, resplendent with feathers and flowers.

Though popular today in Day of the Dead (“Día de Muertos”) festivities, José Guadalupe Posada’s “Skeleton Catrina” satirized decadent Mexican elites who favored European influence and luxury at the expense of their own country. It rebuked a corrupt, exploitative autocracy in the throes of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, a momentous, 10-year cataclysm that transformed the Mexican state, its society and culture. Posada’s Catrina is just one of many intriguing treasures now on display in “Power to the People: Mexican Prints from the Great War to the Cold War,” at the Wichita Art Museum. Headlining the exhibition are examples from Los Tres Grandes, the so-called “Three Greats” of Mexican muralism — Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Guest-curators Cori Sherman North and Bill North culled some 75 works (mostly woodblock and lithograph prints) by 21 artists from the collection of James and Virginia Moffett of Kansas City, Missouri, presented with bilingual wall-text. The result is an outstanding regional exhibition of a local collection that speaks to our cultural and political moment with subtle resonance.

When peace was at last re-established in 1920, the post-revolutionary regime inherited a mandate of social, economic and educational reforms that embraced the rural and Indigenous poor. Revolutionary art, then, celebrated the Indian as foundational to national identity — indigenismo — and demanded forms — murals and prints, inspired by the political ephemera of Posada — that spoke directly and forcefully to political elites and illiterate peasants alike.

Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros were communists who embraced the social justice politics of the revolution in both art and life. They championed indigenismo, yet were deeply influenced by European art, particularly Cubism and Renaissance murals. Although they knew and worked alongside each other, they didn’t always get along, and their distinctive styles and preoccupations appear in striking ways.

Rivera’s prints borrowed scenes from his murals, which celebrate and idealize the Indigenous poor. He spent the revolutionary years in Europe, avoiding bloodshed and turmoil, which might account for the didacticism and romanticization of common people that define his approach. In “Open Air School,” an Indian woman holds an open book in her left hand, teaching. Surrounding her are men, women, children and the elderly, who listen in rapt attention; in the background, peasants plough their fields while a mounted soldier, rifle in hand, looks on.

Orozco drew satirical illustrations during the revolution. His works are more forceful, vehement and expressionistic than Rivera’s. In “The Franciscan and the Indian,” a ghoulish friar looms over the skeletal, wraithlike native he smothers in an oppressive embrace. A young woman clutches the shawl at her breast in “The Soldier’s Wife,” silently prayerful like the Virgin Mary. “Men and Women on the Road” shows displaced soldiers and their families on the move, backs to us, rifles and young children perched on shoulders. In “The Unemployed,” four men sketched in stark stabs of contrasting shade crowd together in dejection without meeting each other’s eyes.

Siqueiros fought in the revolution and was an activist and occasional political prisoner throughout his life. In a pair of hatch-marked cartoons, peasant, soldier and urban laborer clasp hands in revolutionary concord (“Three are Victims, Three are Brothers,”) while traitorous capitalists and politicians (“The Trinity of Scoundrels”) clutch money, not solidarity.

Several color lithographs provide a fascinating glimpse of Siqueiros’ late style, abstract, lean and masterly. “Woman in Jail” depicts an Indigenous peasant with blotted-out eyes, arms and legs constrained in tight folds of clothing, kicking against the earth and space that enclose her. The thick brush strokes and vivid colors of “The Mask” recall a colossal Olmec head, paradoxically evoking monumental permanence and effortless spontaneity.

Contributions from other artists — many who worked with Los Tres Grandes — amplify and sometimes sanitize these themes. Given the prominence of Indigenous women in Mexican muralism and prints, the absence of female artists is striking. The sole contribution here is “Girl with a Basket,” by Polish-born Fanny Rabel, who studied with Frida Kahlo and apprenticed with Siqueiros and Rivera. A bonneted baby girl leans against a basket, dark eyes staring out, face fixed in a frown. The revolution devastated families and children.

Two portraits of Emiliano Zapata, revolutionary peasant leader of agrarian reform, distinguish the approach and concerns of Rivera and Siqueiros.

Brow furrowed, Rivera’s Zapata is stern but open hearted; his white horse (the Mexican people), regards him adoringly. He and the men following him wear sandals and traditional campesino white, armed with farming tools. He steps with determination on the saber of a fallen government soldier beneath him. Lush foliage rises all around, linking them to the land. This is the hero of the people, shepherding the promise and fulfillment of the revolution.

Siqueiros’ Zapata is a dark, solitary horseman, eyeing the field beyond the frame with caution and distrust, rifle tucked in saddle. He seems backed into a corner, a sea of hills looming behind. There is no way forward, no going back. This is the Zapata gunned down in a 1919 assassination plot, a symbol of the people betrayed by a regime turning its back on the revolution.

Each saw what the other missed.

As WAM’s Prairie Print Makers collection demonstrates, prints and printmaking have a notable tradition here in Kansas, but this exhibit drops at a particularly suggestive moment.

Just as the Mexican Revolution created a new consciousness for social justice in art and society, public outcry in this country over the unequal impact of the pandemic and police violence on people of color and the poor has spurred on Black Lives Matter protests, sparked debates over critical race theory and catapulted questions of diversity, equity and inclusion to the forefront of our national conversation, in work, art and in politics.

Though the parallels should not be pressed, they are nonetheless worth pausing over.

“Power to the People: Mexican Prints from the Great War to the Cold War,” continues at the Wichita Art Museum, 1400 West Museum Blvd., Wichita, Kan., through Dec. 31. Also on view at WAM through Sept. 25 is “All in Time,” a 20-year retrospective of artist Beth Lipman, noted for probing still lifes in glass and mixed materials that explore issues of life and death, creation and decay. For more information, 316.268.4921 or wichitaartmuseum.org.